SAN ANTONIO — A tender yearning permeates the traveling career survey of Bronx-born Whitfield Lovell, who forges Black histories from aged photographs. The exhibition begins with Lovell’s works about family and biography beginning in the mid-1980s. At the belly of “Grandma’s Dress” (1990), a Black Indigenous woman half reclines while surrounded by palm trees — part Virgin Mary, part Venus of Urbino — holding a palm frond, a symbol of victory overcoming death. Around the dress, wet green shoots into frenetic arcs, like moving palms. Lovell’s paternal side comes from Barbados; this work celebrates the far origins of the Black Atlantic, and sets the tone of the exhibition’s concern with the search for community and ancestries.

In the next room, the smell of nutrient-rich earth and decomposing tree bark, like the scent of sweet cloves, subtly envelops the viewer. The sounds of running water and chirping birds accompany the scents, suggesting change, or a sense of crossing over. Entitled “Deep River” (2013), the work envisions the conditions for runaway slaves during the Civil War, many of whom traversed the Tennessee River to find asylum in the Union Army’s “Camp Contraband” in Chattanooga, Tennessee. At the middle of the installation is a large mound of earth, strewn with bottles, lamps, musical instruments, bibles, and guns, and encircled by turned wooden discs on which Lovell has painted portraits of Black people from the Civil War onwards. A pile of suitcases is stacked against the wall, above which is a portrait of a man holding keys, a symbol of freedom. Video projections of undulating waves flittering in sunlight resonate with a palpitating sense of longing.

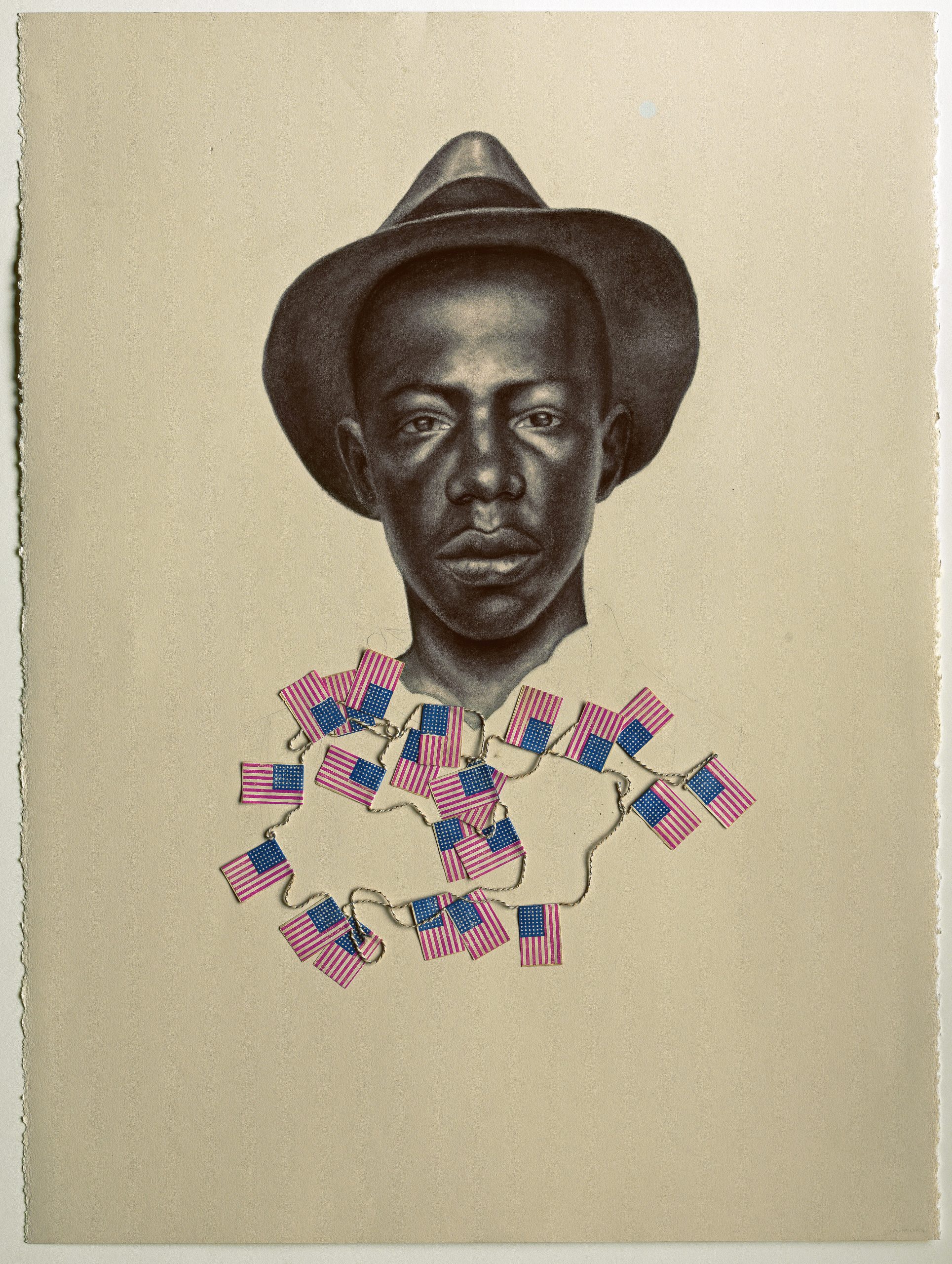

Across his photo-based works, Lovell quarries lost origins through varying types of Black archival imagery. In the Kin (2008–11) series, for instance, he recreates images from photo booths and IDs from between 1850 and 1950 in charcoal. In Card Pieces (2020–21), Lovell has matched each playing card with the frontal portrait of a person with humor and care: The Queen of Hearts, for instance, is a regal woman who looks off into the distance. Among his tableaux, Lovell depicts a man in three-quarters view in “Wreath” (2000), surrounded by a barbed nest out of concentric rusted steel, as protection against hurt. Nearby, in “For…” (2008), a woman eyes the distance as globes orbit about her, laved in the same green as “Grandma’s Dress,” similarly conveying and closing distances.

The show ends with Visitation (2001), commemorating Jackson Ward of Richmond, Virginia, the United States’s first major Black entrepreneurial community, founded in the 1860s. With the large tableau “Our Best” (2001), Lovell depicts the beginnings of the Black Southern middle class via life-sized portraits on recycled wood that refuse the persistent period imagery linked to sharecropping and the Civil War. And for the installation “Visitation: The Parlor” (2001), he sets softly lit place settings and lace, smelling faintly of stale whiskey and tobacco, around a dining table. An old radio plays blues and gospel next to a stack of Richmond newspapers dated to 1908. Two figures dressed in turn-of-the-century garb face one another from opposite walls of the room, as if the progenitors of this scene of family and community, the same tender heart of all of Lovell’s reconstitutions.

Whitfield Lovell: Passages continues at the McNay Art Museum (6000 North New Braunfels Avenue, San Antonio, Texas) through January 19, 2025. The exhibition was organized by the American Federation of Arts in collaboration with Whitfield Lovell. This iteration of the exhibition was curated by René Paul Barilleaux and Lauren Thompson.