SANTA FE — The introduction to George Chauncey’s Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890–1940, a history of the city’s pre-Stonewall gay underground published in 1994, contains a challenge to other historians. The author brings up “scattered evidence” of early-20th-century gay subcultures in a “handful” of other American cities. He mentions Chicago and Los Angeles by name, but doesn’t rule out small towns that “also sustained gay social networks of some scope.” Then Chauncey lays down the gauntlet: “We should never presume the absence of something before we have looked for it.”

When he started his research in the 1980s, Chauncey was one of two American scholars — that he knew of, at least — writing dissertations on LGBTQ+ history. In a new preface for the 2019 paperback edition of Gay New York, he celebrates the “astonishing growth” of the field. “The local community study is no longer the dominant form in queer history or in other fields of history,” he declares.

Things look different in the opposite corner of the country. Santa Fe, New Mexico has long been a gay epicenter of the Southwest, but cultural practitioners here still face a steep challenge when it comes to illuminating regional LGBTQ+ histories. There’s a lot of historical excavation to do, and not as many hands to help dig.

Beyond posterity, what is the value of preserving and sharing regional queer histories? This year, an author and a museum curator in Santa Fe serendipitously aligned in their respective pursuits to answer this question. Armed with a remarkable memory and a quiver of juicy anecdotes, Walter Cooper spent years researching and writing his memoir Unbuttoned: Gay Life in the Santa Fe Arts Scene, which he self-published in 2016 and updated last year. And nearly contemporaneously, Christian Waguespack was gestating the current group exhibition Out West: Gay and Lesbian Artists in the Southwest 1900 –1969, at the New Mexico Museum of Art.

At 84 years old, Cooper has lived in Santa Fe for 50 years, having arrived in 1973 after a closeted and stress-ridden stint as a New York adman. “I’m kind of surprised that I’m still here, period,” he says. “I’m one of the last people around.” By “people,” he means gay folks of a Santa Fe heyday: the swinging 1970s, ‘80s, and ‘90s, a time when some prominent denizens of the midcentury Santa Fe Art Colony, such as Janet Lippincott, Thomas Macaione, and Agnes “Agi” Sims, were still around, and a new generation of artists was on the rise.

“It was kind of a wild time,” says Cooper of the ‘70s. “I had an early introduction to a lot of people who were major players in the gay scene and the art scene. There were lots of dinner parties, after-show parties.”

Though Cooper crosses paths with some New Mexico-linked celebrities in his book — Georgia O’Keeffe, Agnes Martin, Shirley MacLaine — they serve as set dressing for a cast of local artists bound for regional fame. For example, a secondhand account of Andy Warhol’s 1977 art opening in Santa Fe, for which Cooper didn’t land an invite, centers on Indigenous artists Ron Robles and Armond Lara (who are gay and straight, respectively). Warhol spots Robles’s gold bear claw necklace and remarks, “I thought Indians only wore silver.” Robles cheekily retorts, “Silver? You eat off silver. You don’t wear it.” Thus, an anecdote that might’ve been packaged as a quirky footnote in a broader LGBTQ+ history is told from the perspective of an Indigenous, queer protagonist — a tribute to the particular power of regionalism and the “local community study.”

During the writing process, Cooper says, the scope of his narrative started to expand, along with his motivations. “At first I was just writing about my time period, the ‘70s through the ‘90s, but I needed to include prehistory for that,” he explains. “And I just realized that nobody had written about [Santa Fe’s gay history], not in any depth.”

In Unbuttoned, Cooper weaves in tales of an older generation of artists whom he developed friendships with, such as Sims, an artist from Philadelphia who arrived in 1938 and cultivated a lesbian clique that included photographer Laura Gilpin and O’Keeffe’s longtime ranch hand Maria Chabot. Dialing back the clock also allows Cooper to include fun anecdotes such as Truman Capote declaring Santa Fe “the dyke capital of the world” after visiting Sims and her longtime partner Mary Louise Aswell, the fiction editor of Harper’s Bazaar, in 1976. Cooper also covers LGBTQ+ Santa Fe hotspots such as the midcentury gay saloon Claude’s Bar; out-of-the-closet Santa Fe art colonists such as Cady Wells and Witter Bynner; and under-the-radar queer activities by famous turn-of-the-century figures like Taos arts patron Mabel Dodge Luhan and British author and brief New Mexico transplant D.H. Lawrence.

Many of those same people and places weave themselves into Waguespack’s exhibition as well. “I was curating a little backwards,” he says. “Instead of coming up with the idea and doing the research, it was years of collecting these stories.” It started with his work on a solo exhibition for the Massachusetts-born Wells, who landed near Santa Fe in 1932. He was close with O’Keeffe, who called him “one of the two best painters working in our part of the country,” according to Cooper’s book.

“For [Wells] to be able to live [as an out gay man] during this time period was a bit of a revelation for me,” says Waguespack. As he mapped Wells’s circle, and then the larger scene, he was amazed by the number of gay and lesbian artists who had helped shape Santa Fe’s modern reputation — and the fact that their collective story had never been told through a queer paradigm.

“It’s like somebody dropped a bucket of tiles and, look, there’s the mosaic,” Waguespack says. “I don’t take credit for trailblazing research… those stories were all there for anybody who wanted to look towards them. But just taking the time to bring all of them together in one place was really the project.”

That’s how Waguespack linked up with Cooper, whose memoir was so influential to Out West that it’s quoted near the exhibition’s title wall. The excerpt reads, in part, “People tend to underrate or ignore ‘the queer factor,’ the enormous impact gay folk have made on New Mexico’s unique cultural life.”

Like Cooper, Waguespack combines the early 20th century with the more recent in his storytelling, and draws on personal connections. He titled the show after Harmony Hammond’s curatorial project Out West, a 1999 exhibition of contemporary gay and lesbian artists in Santa Fe at Plan B Evolving Arts. The Galisteo, New Mexico-based artist has been another mentor for Waguespack, and her 1997 installation “What Have You Done with Our Desire” is an outlier in his show’s timeline that smooths the passage to more distant eras, like Cooper’s friends and their tales of the past.

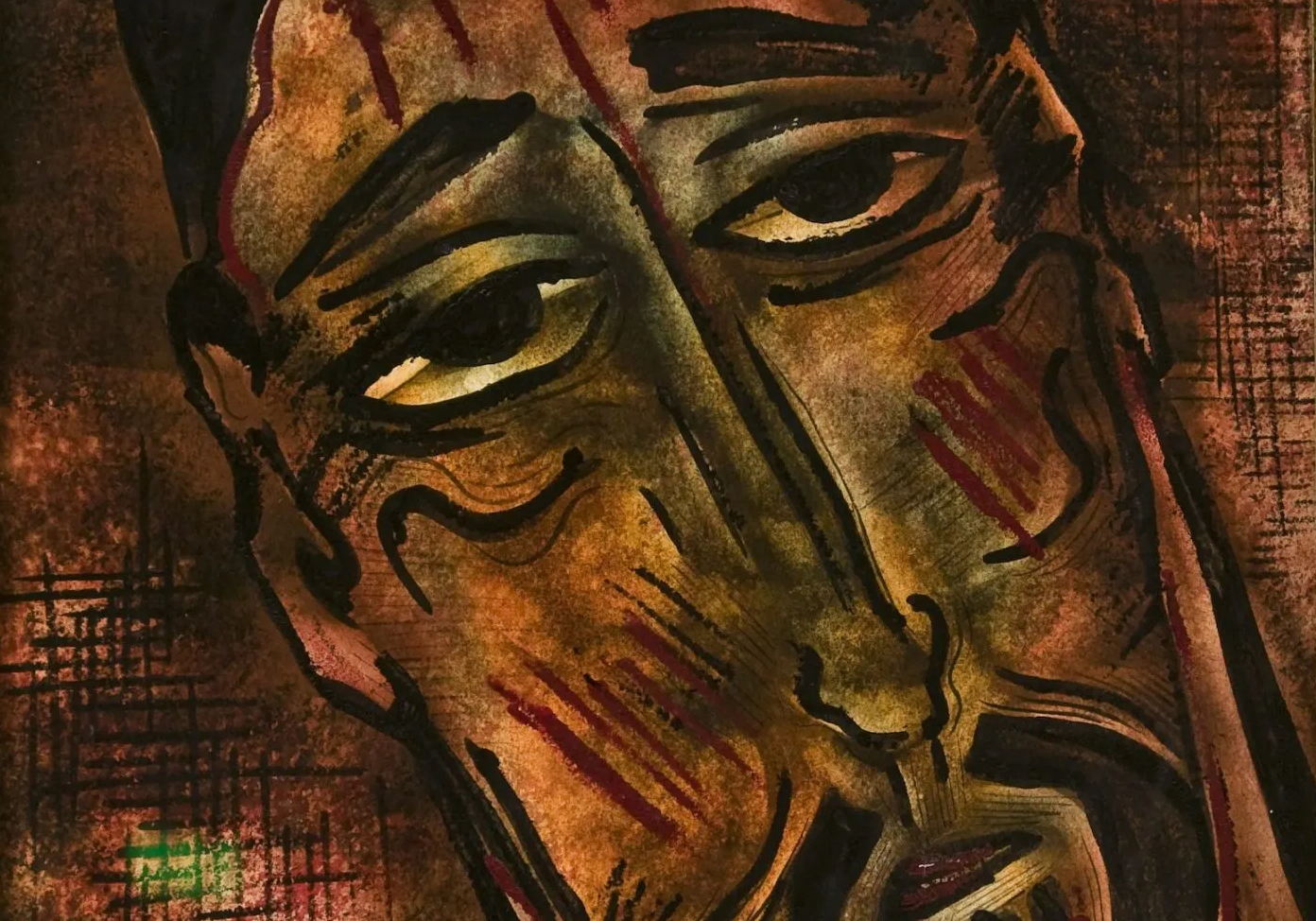

The main arc of Waguespack’s Out West paints a picture of Santa Fe as a safe haven for queer, early-modern artists. National icons including Martin and Marsden Hartley appear with local legends such as R.C. Gorman and Will Shuster.

“Santa Fe was where you came if you were less established, more experimental, more bohemian… and that appealed to a lot of queer people,” says Waguespack. “[They] were interested in not only being artists, but also living a life that was pointedly different.”

In the same breath, he cautions against matching these historical figures with modern conceptions of being “out.” He adds: “Santa Fe offered some freedoms that other places didn’t, but it wasn’t carte blanche …. It did take bravery to [openly express gay identity].”

Out West also traces queer threads of regional Indigenous history. A remarkable pair of late-1800s photographs by John K. Hillers depicts We-Wha, a Two Spirit person, or an individual in the Zuni tribe who took on both male and female tasks. We-Wha was a pottery and textile artist as well as a cultural ambassador who visited Washington, DC, and met President Grover Cleveland in 1886. Hillers’s black and white portrait of We-Wha at their backstrap loom, shot through the suspended warp, is perhaps the most striking and poetic image in the exhibition. One can almost hear the twang of the loom’s threads due to the crystalline immediacy of the photograph, setting it apart from other historical portraits in the show. Here is a fully formed queer figure of the past, crashing through the history books to challenge modern-day assumptions about the range of late-19th-century public gender expression.

Waguespack, who is a millennial, says he “felt an enormous amount of pressure” in engaging elders like Cooper and the 80-year-old Hammond in the curatorial process. “The trail wasn’t set yet, so we had to figure out… how are we going to tell these stories and where are we getting the stories from?” Waguespack says. “There was a constant fear that I was missing someone.” He was determined to tap threads of living memory while they’re still around, so that Out West could serve as a small but vivid starting point for future queer-centric explorations of Southwestern art history.

“Curating early-20th-century artwork means a lot of archival research, which is predicated on what people feel like is valuable for an archive,” says Waguespack. “What particularly resonates with queer people is that you have to have a family or someone left after you die to save this information and champion you. A lot of these artists didn’t have that.”

What they do have, for the moment, are queer descendants like Cooper, Hammond, and Waguespack — a hyperlocal lineage of chosen family.

In Gay New York, Chauncey discusses how each generation of historians tends to feed the next, like an ouroboros. “History shapes the way we read — and write — history,” he writes. In one sense, the regional histories of Out West and Unbuttoned form a tight loop of influence. But in relation to national histories, they hang outside of a larger cycle, offering fresh and disruptive threads for a new generation of historians to discover — as long as they’re looking for them.