CHICAGO — Robert Earl Paige is having a moment. At the age of 87, the South Side icon has had a lifetime of them, but this is one of those rare the-art-world-is-paying-attention moments, and it feels joyful and deserved.

The indefatigably optimistic and dapper Chicagoan is being celebrated by the Hyde Park Art Center with The United Colors of Robert Earl Paige, the largest exhibition of his work to date, featuring textile designs, fabric paintings, murals, and recent ceramics, selected from seven decades of making. The show follows on the heels of Power to the People, Paige’s well-received New York solo show, curated by Nigerian fashion designer Duro Olowu at Salon 94 Design in the fall of 2022. Upcoming this September is Give the Drummer Some!, Paige’s graphic takeover of the University of Chicago, when his distinctive patterns will spread from the Smart Museum lobby outward, eventually covering coffee cups, banners, benches, and planters across the entire campus. Also this fall, Paige’s pioneering designs for the home will be included in the Smithsonian Design Triennial at the Cooper Hewitt.

The United Colors of Robert Earl Paige is as beautiful, bright, and hopeful as an exhibition can be. The entrance is framed by Paige’s snazzy wallpapers, overlapped to look like gift wrapping, making of the entire show a present to the viewer. Inside, the cavernous main gallery of HPAC thrums with the vivid colors and abstract patterns that the artist has been fashioning since the early 1960s, in his signature fusion of modernist principles and African motifs. The walls are covered in giant, sunshiny murals and hung with a decades-spanning selection of his collages, scarves, hand-painted silks, and drawings. Samples from years of work as a commercial designer are displayed on elegant wooden tables. Scrappy assemblages of rocks, cardboard, and bottle tops pop up here and there. A stripey weave, like a chic rainbow, upholsters room dividers and covers the pillows strewn on a cozy couch. A sprawling navy and dusty rose rug in an unfathomably elegant pattern of mismatched shapes covers the floor. At the center stands an open-roofed workshop space in deep lilac with cleverly cut-out walls.

The overall effect is comfy and welcoming in a way that has become common as museums institutionally assume the mantle of social practice and relational aesthetics. But Paige has been doing it all along. Being in his retrospective feels like being in the home of someone who loves art, finds it everywhere, and wants you to enjoy it too. This has much to do with the artist’s particular philosophy of beauty. “I look at everything,” he has said, “and I think that hopefully you can rid ugliness with beauty. People need beauty, they need to be inspired. Beauty is a basic service.” The open-armed vibe is also rooted in the fact that the exhibition is filled with actual items of home decor, and that visitors are allowed to experience them as such — sitting on the soft sofa, noticing the attractive art on the wall behind it, digging toes into the plush carpet, wearing one of a dozen vibrantly hand-painted scarves. Well, you can’t actually try on the scarves, but it’s hard not to imagine doing so, or sewing an outfit from the yardage of fabulous fabrics billowing from the ceiling, designed by Paige for Walmart in 2003.

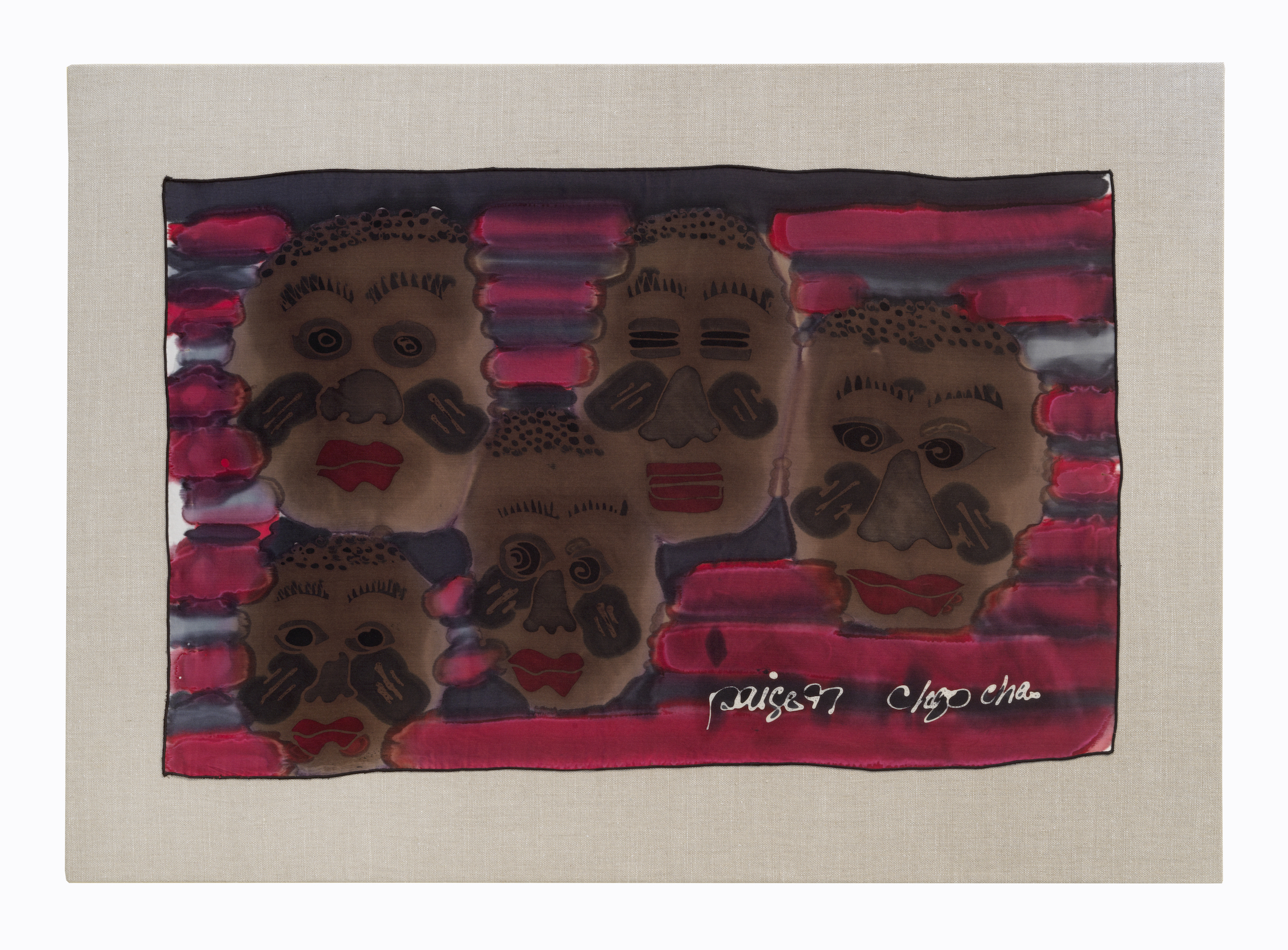

Yes, Walmart. The accessibility is classic Paige, as are the patterns: riotously bold backgrounds, one of many nods to Mondrian, Sonia Delaunay, Matisse, and other modernist masters of color and geometry, overlaid with line drawings inspired by African masks and symbols. Decades earlier, in 1973, Paige made history doing something similar, and at the time quite radical, when Sears Roebuck & Company released his Dakkabar Collection. A series of stylish home textiles inspired by African-American heritage and culture, and meant to appeal directly to Black consumers, it was sold in 56 cities and 130 stores across the United States. Samples are on view here.

The political importance of that commercial work jibes with the local communities to which Paige has always belonged. A longtime resident of the Woodlawn neighborhood, he got his start working at the architecture firm Skidmore Owings & Merrill and trained at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. But he has long been known for giving out keys to his studio to promising younger artists, and in the 1960s and ’70s Paige was part of Chicago’s Black Arts Movement and an early member of the AfriCOBRA collective, helping to cultivate a Black aesthetic largely absent from the mainstream. Together with arts educator Dr. Carol Adams, he founded Everyday Art, offering community art programming, presenting art in workaday places like laundromats, and planning the first Black arts festival at the South Shore Cultural Center.

And the collaborations have never stopped: The United Colors of Robert Earl Paige features furniture made with Jeffrey Robinson, murals painted by Dorian Sylvain, textiles designed with the Weaving Mill, and Parapluie, a companion exhibition filled with harmonious artworks by his ever-expanding cohort of peers. The workshop built in the very center of the gallery, where Paige leads free multigenerational sessions with Keny De La Peña, will no doubt widen the circle even further. The day I was there, participants were making watercolors using Kool-Aid, in a nod to the vibrant “cool-ade” hues of AfriCOBRA, a concept that originally came from Paige and that remains as agelessly cool and full of glee as the man himself.

The United Colors of Robert Earl Paige continues at the Hyde Park Art Center (5020 South Cornell Avenue, Chicago, Illinois) through October 27 . The exhibition was curated by Allison Peters Quinn, director of Exhibition & Residency Programs, in collaboration with the artist.