With Life Dances On: Robert Frank in Dialogue, the Museum of Modern Art makes what might seem like an unusual decision: to stage its first-ever solo exhibition of Robert Frank while largely omitting his best-known body of work, The Americans. Published in the United States in 1959, with an introduction by the Beat writer Jack Kerouac, The Americans is arguably the most influential book of American road photography in the history of the medium. When one thinks of Frank today, these are likely the images that come to mind: faces looking out at us from the segregated New Orleans trolley car on the book’s cover, an American flag obscuring a woman’s face as she stands in a window, Frank’s critically distanced vision of an unequal consumerist society decked out in stars and stripes and automobiles as it rose to global cultural dominance after World War II. The Americans also paved the way for a new aesthetic approach to the “documentary” genre, embracing blur, grain, crooked framing, and muddy shadows. MoMA’s exhibition acknowledges this pivotal moment in the history of photography, nods to it, and then moves on — and thank goodness for that.

Life Dances On is true to its title, demonstrating that if anything, Frank’s work became more interesting after his magnum opus. Just as The Americans was beginning to make waves in the photography world, he turned to filmmaking, collaborating again with Kerouac and other Beat poets on his first film, Pull My Daisy (1959). Frank became a significant independent filmmaker at a time when experimental cinema was taking off in the United States, and MoMA highlights this major aspect of his career in two other separate presentations: Robert Frank’s Scrapbook Footage, which concurrently presents his more intimate, diaristic moving image work, and The Complete Robert Frank: Films and Videos 1959-2017, a retrospective of his film and video work screening between November 20 and December 11.

The most fascinating aspect of this exhibition, however, is its focus on how Frank alternated between the two poles of still and moving image, blurring the boundaries between media. Life Dances On would be worth seeing simply as a superb example of how to integrate photography and film into a gallery space — something that so many museums still struggle with as they move past painting’s art historical monopoly.

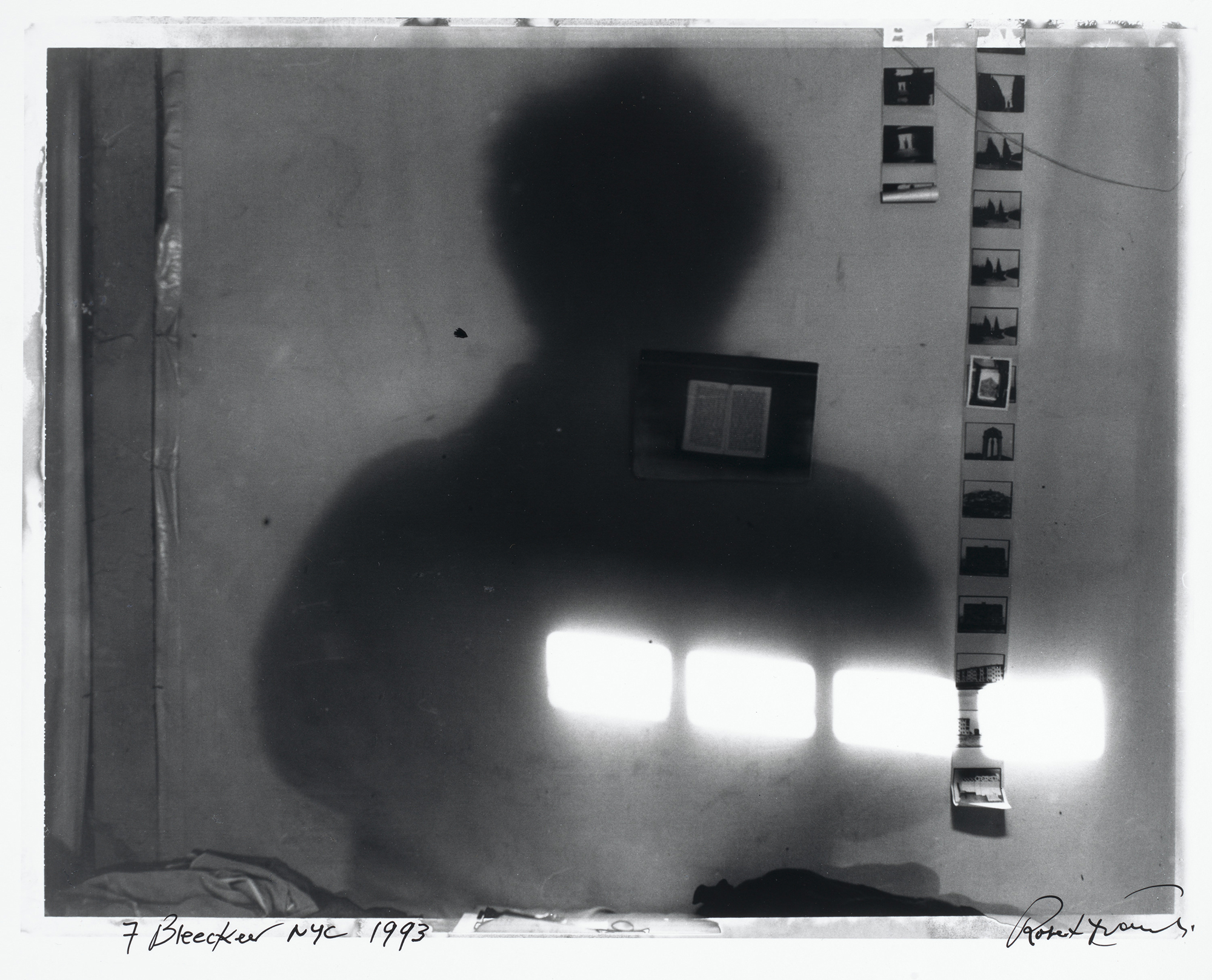

As the 1960s and ’70s progressed, Frank became increasingly interested in darkroom experimentation, playing with the materiality of the image and collaging film strips together on one single photographic print. “Mabou Winter Footage” (1977), for example, both channels early experimental cinema — recalling the disembodied eyes of Hans Richter’s 1928 Filmstudie — and pushes the boundaries of what a photograph can be. Frank sutures photographs together, taping them into panoramas or writing directly onto their surface, echoing contemporaries like Duane Michals and Robert Rauschenberg. Many of his later works hint at narrative, such as “Sick of Goodby’s” (1978), which was made after the death of his daughter, Andrea, and of his friend, Danny Seymour. Such image sequences feel both cinematic and handmade, melancholic yet somehow less alienated than The Americans. As Frank got older, he continued to keep up with the times, venturing into video and larger format color prints. This refreshing exhibition demonstrates that, far from being overshadowed by The Americans, Robert Frank was only getting started with it.

Life Dances On: Robert Frank in Dialogue continues at the Museum of Modern Art (11 West 53rd Street, Manhattan) through January 11, 2025. The exhibition was organized by Lucy Gallun, Curator, with Kaitlin Booher, Beaumont and Nancy Newhall Curatorial Fellow, and Casey Li, Intern, Department of Photography.