Bea Lema does not shy away from the vulnerability of autobiography. The Galician artist and writer’s moving new book El Cuerpo de Cristo (The Body of Christ) parallels her own life growing up with a mother who suffered from severe mental illness. Illustrated in marker and thread, the book follows the young Vera, who desperately wants to protect her mom Adela from the demons who torment and even threaten to end her life. Though centered on a single family’s pain, El Cuerpo de Cristo is also the story of women’s experiences across three generations in Galicia, Spain, offering a more universal meditation on trauma, caretaking, and shame.

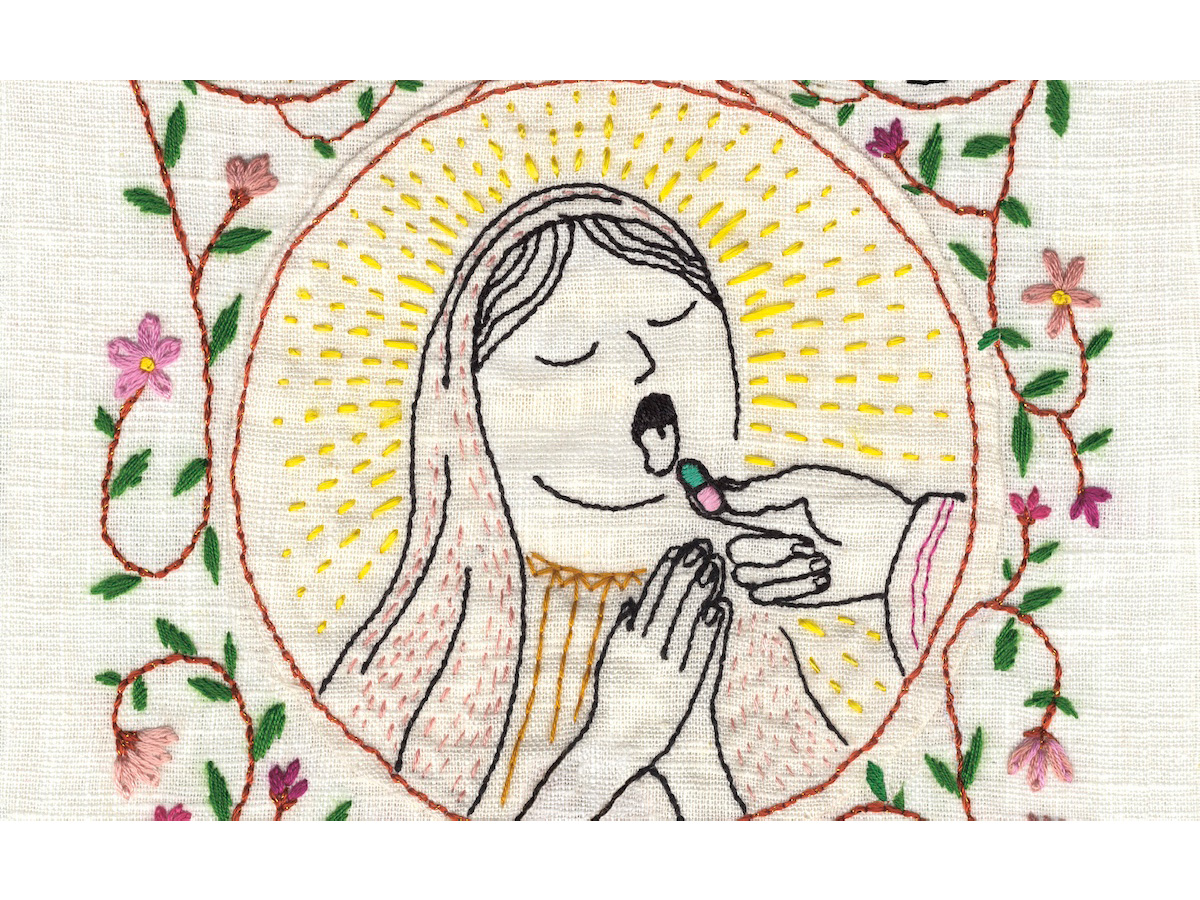

Stories like Lema’s are often suppressed by society, but El Cuerpo de Cristo suggests that society is often what contributes to illness in the first place. The narrative jumps between Vera’s youth in the busy port city of A Coruña in the 1980s and ’90s and her mother’s small village in the Costa da Morte during the dictatorship of Francisco Franco. Vera’s life is drawn in pastel marker, while flashbacks to her mother’s past are sewn in black thread, with the latter echoing the late painter Castelao’s depictions of rural Galicia from the early 20th century. Vera’s mother is dominated by her abusive and alcoholic father. Later, married and living in the city, she’s confined to child-rearing, housekeeping, and sewing. Adela’s debilitating illness is met by an ineffective medical system, where a string of doctors — all men — endlessly diminish and mishandle her pain. Faced with a lack of clear solutions, Adela turns to religion for relief.

Lema showcases aspects of her homeland’s culture throughout the book’s rich illustrations — including nods to Galician mainstays like Sargadelos porcelain and Bonilla la Vista potato chips — but Adela’s religious fervor gives readers insight into the region’s especially unique spiritual life. Galicia has been a site of religious pilgrimage for centuries, and its deep pagan and Celtic roots have infused its Catholicism with a sense of mysticism, especially in rural areas. Vera visits a folk healer and attends the procession of Santa Marta de Ribarteme, where those who have miraculously avoided death were paraded in open coffins (the ritual has recently been stopped). In another scene, the mother tries to exorcize her demons at the Santuario de Nosa Señora de O Corpiño, to no avail.

Though most of the El Cuerpo de Cristo is rendered in marker, Lema embroiders passages that deal with the mother’s harrowing past and most intense points of psychosis. These are often the most tragic moments in the book, but the sewing imbues each page with a sense of ongoing care: After all, the process of embroidery requires touch, time, and tenderness.

Though she’s only a child, Vera takes on the enormous emotional weight of her mother’s illness. After yet another blow-up, this time because Adela has started drinking to combat her condition, Lema depicts little Vera among her toys, cradling her doll-sized mother in her arms. The heartbreaking role reversal is captured only by this image and simple text on the spread: “Yo te cuido, Mamá” (“I’ll take care of you, Mommy”). Years go by, and Vera is still the principal caretaker for her mother while her older brother and father remain painfully out of touch. Lema dedicates the latter part of her book to the struggles of caretaking, both imbalances between demands on men and women and the difficulty of looking after oneself while caring for another.

In September, El Cuerpo de Cristo was named the winner of Spain’s Premio Nacional del Cómic. I attended a panel discussion that featured Lema at a bookshop in A Coruña a month later, and was struck when one of the audience members pointed out that the author was only the second woman to win the award. Founded by the country’s Ministerio de Cultura in 2007, the prestigious prize was granted to Ana Penyas in 2018 for her work Estamos todas bien (We Are All Okay). At that time, according to a survey of major comic prizes in Spain, more than 90% of awards since the 1980s had historically gone to men.

Both authors were recognized for works that shed light on women’s often-overlooked stories: Penyas on the generation of women who survived the Spanish Civil War and the sexism that followed it, and Lema on the complexity of mental illness, family life, and healing. El Cuerpo de Cristo tells a story we don’t often get to hear, and does so in the unconventional, highly personal language of ink and thread. As with Vera in the story, Lema learned to sew from her mother, who in turn learned it from her own mother. Though often labeled “women’s work,” sewing is both an art and an essential tool for mending, repairing, and embellishing. In this way, it’s a meditative form of caretaking that extends the life of something held dear, while offering its creator the space for mental peace.

El Cuerpo de Cristo (2024) by Bea Lema is published by Astiberri Ediciones and is available online and through independent booksellers. A French version of the book was published by Éditions Sarbacane as Des maux à dire.